Every morning after Jiro showers, he spends over an hour on his daily beautification routine. Facial cleansers, moisturizers, toners, creams, hair gel and body sprays line the shelf just below the wall-mounted mirror in his single room apartment “unit bath” washroom. After this ritual, it is not uncommon for him to painstakingly compare shirt, pant and shoe combinations before deciding on today’s “look.”

While such a morning regimen would have been next to unthinkable for men to willingly adopt a decade ago, more and more, extensive attention to appearance using cosmetics and beauty products among men is becoming the standard rather than the exception. Nowhere is this phenomenon more pronounced, perhaps, than in Japan.

But what are the social forces at work that are influencing this massive exodus from the realm traditionally defined as “masculinity?” Is it merely the result of cleverly designed marketing campaigns produced by the beauty and cosmetics industry, a fad that men will “grow out of” in the coming years? Or is this a manifestation of a much more significant change in the values that constitute masculinity, a paradigm shift in gender roles?

Aggressive marketing of beauty and cosmetics products in recent years has undoubtedly played a significant role in the expansion of the men’s beauty and cosmetics category. Global brands have increasingly focused efforts on Japan as well, making significant inroads into the market sector.

While skillful marketing strategies have been an important step in bringing the advantages of cosmetic and beauty product use to the forefront, however, we would be mistaken to assume that product promotion alone is responsible for this phenomenon. Marketing campaigns would not have been nearly as successful had there not already been an underlying need among men becoming more concerned with their appearance.

If not a result of promotional efforts, then, to what do we owe this shift of values among men, and when did extensive attention to one’s appearance become a perceived need? To better understand the changing values of men and scope of masculinity, we first must turn to, (surprise) women.

Historical Perspective:

A brief history lesson may be in order at this point, to set the stage for an explanation of changing women’s roles in Japanese society, and what this means for men.

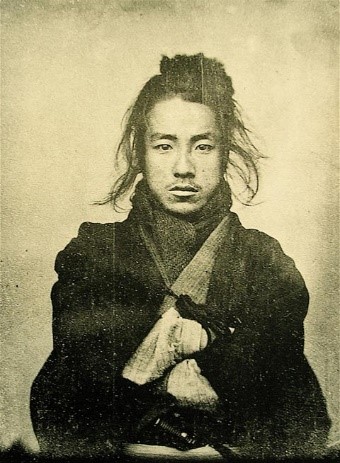

Heavily influenced by Confucian and Buddhist thought, from the 1600’s Japan was an agrarian society governed by a form of samurai-based feudalism. Women during this time were considered inferior to men and were to be subservient to father, husband, and son. Their role was primarily limited to housework. When initial experiences with foreign interests did not go well for Japan, the resulting period of isolation meant that traditional social values went virtually unchanged until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Feudalism and samurai law was abolished, at the same time industrial modernization became Japan’s central priority. During this time, women were told they had the moral duty to “umeyo fuyaseyo,” or give birth and raise children. In the time leading up to WWII, women filled the increasing need for factory labor, continuing on to fill the gap left by men during the war. They failed, however, to realize a significant improvement in social position. In the post-war reconstruction period, there was a natural “leveling” of the social structure in favor of democracy. This, in concert with McCarthur’s “essential equalities” edict, was a huge step in establishing equal rights and augmented roles for women.

After the implosion of the “bubble economy,” guaranteed lifetime work to (male) corporate employees vanished. Men could no longer be relied on exclusively as providers, thus women increasingly endeavored to develop their own careers and establish their own financial independence.

Changing Women’s Roles:

While significant gender inequalities remain today, the burgeoning financial independence of women in Japan has impacted the perception of gender roles and relations. Women choose their own partner rather than relying on arranged marriages, and now wait much later to marry. There is more equality in relationships, with women maintaining authority over child-rearing and family finances, while continuing to work until, and even after, childbirth.

Changing Women’s Needs:

As a result, standards for selecting a mate have shifted significantly. Whereas, factors such as “financial stability,” “bravery,” and “chivalry” have been found to be diminishing in importance, softer qualities such as “kindness,” “sensitivity,” and “appearance” are increasingly emphasized by women.

No longer in need of a partner for financial stability, and increasingly unconstrained by traditional roles, women are increasingly choosing their partner based on “softer” characteristics related to personality and appearance (imagine that).

Changing Values of Masculinity:

It would not be long before Japanese men began catching on to this significant values shift among women. In this sense, the trend toward emphasis of “softer qualities” among men can be thought of as “reactionary,” adjustment to meet the demands of environmental factors over which they themselves had little control.

Beyond advertisements, major media outlets have reinforced the image of the “soushoku” (herbivore) man. The Yaoi “Boys’ Love” manga genre, boasting a wide audience among middle school age and older women, focus exclusively on depictions of “softer” masculinity with plots that inevitably lead to homoerotic situations. Boy band idol group members, such as those belonging to Johnny’s Entertainment, have also been noted as becoming increasingly effeminate in recent years, both in looks and expressive style. Many boy band talents are also featured in popular TV dramas, movies and advertisements, further expanding their reach and thus the impact of “androgynous” masculinity.

Beyond advertisements, major media outlets have reinforced the image of the “soushoku” (herbivore) man. The Yaoi “Boys’ Love” manga genre, boasting a wide audience among middle school age and older women, focus exclusively on depictions of “softer” masculinity with plots that inevitably lead to homoerotic situations. Boy band idol group members, such as those belonging to Johnny’s Entertainment, have also been noted as becoming increasingly effeminate in recent years, both in looks and expressive style. Many boy band talents are also featured in popular TV dramas, movies and advertisements, further expanding their reach and thus the impact of “androgynous” masculinity.

As men who follow extremes in the “soushoku” path can sometimes be indistinguishable from women, one may question whether this is really “what women want.” A recent study by Fabienne Darling-Wolf at Temple University addressed just this issue. Through a series of interviews with women of all ages in Japan, she probed women’s feelings regarding the increasingly effeminate “soushoku” men, focusing on “idol” personalities in the entertainment industry. Interestingly, she found that by and large, women find these “effeminate” men to exhibit strong, favorable masculine traits. However, their masculinity has much less to do with their “effeminate” appearance specifically, and more to do with the perceived “bravery,” the determination it takes for a man to be kind and sensitive, to show his feminine side despite being outside the scope of traditional masculine boundaries. In other words, it takes a real man to act like a woman.

While this sentiment was found to be fairly constant across age groups, when women were asked if they would consider such men as a romantic partner, mid through older women indicated that, while they found the “feminine” men to be attractive, their interest would not go beyond the platonic. Conversely, some younger women, while giving decidedly ambiguous responses, expressed receptivity to a romantic relationship in some cases. This can be interpreted as potentially a function of changing social values. While middle age to older women who were brought up during a time before the role of women (and subsequently masculine values) made such an abrupt shift, younger women who are growing up knowing only the power and possibilities foreign to previous generations, find attractive, men who care for their appearance (even to the point of bordering on “androgynous” in some cases) ideal as a romantic partner.

Thus, while the skillful placement and marketing campaigns by the cosmetic and beauty industry have played a significant role in the promotion of the “softer side of masculinity,” increasing emphasis on external beauty, as well as “softer” personality and emotional values as “masculine” is not merely a Shibuya fashion statement that has caught on temporarily. Rather, the rise of “soushoku” masculinity can be considered a factor of women’s changing role in Japanese society, how new roles have affected the values they look for in men, and how men, in turn, have adapted.

With this in mind, cosmetics, health and beauty, indeed manufacturers of all related lifestyle products, would do well to take a closer look at the market for Japanese men. The “beautification” of masculinity in Japan is not likely to fade away any time soon.